A Simple Routine

To Improve Your Software's Resiliency

We have to try to cure our faults by attention and not by will.

Simone Weil

Have you ever been surprised to find out your system is degraded? Have you ever been embarrassed when a client asks in your Slack channel why your system is down? Have you ever written a high-quality API, only to find out months later that its performance has degraded or billing has swelled to unacceptable levels?

I’d like to share a quick routine that improves system reliability, resiliency, and performance. It is not a hypothetical, untested routine. The teams I lead at The New York Times adopted and use it daily to improve the quality of our production, user-facing, business-critical systems. It keeps us effectively serving our paywalls, choosing personalized offers, and serving landing pages that support our business goals.

Why a routine?

All production systems should be backed with a robust set of observability tools. These often include traces, profiling, logs, metrics, dashboards, alerts, and more. Together, these tools give us insight into what our systems are doing and how well they are doing it. Sometimes, there are completely automated ways of evaluating our systems. For example, you may use Datadog’s Watchdog or Anomaly Monitors. These tools automatically watch for and can even alert you to anomalous behavior in your systems.

However, no matter how good our algorithms get, no alerting strategy is perfect. Things always slip through the cracks. If we place too much trust in automated monitoring and alerting—by not manually checking our systems’ performance—we risk allowing issues to go undetected.

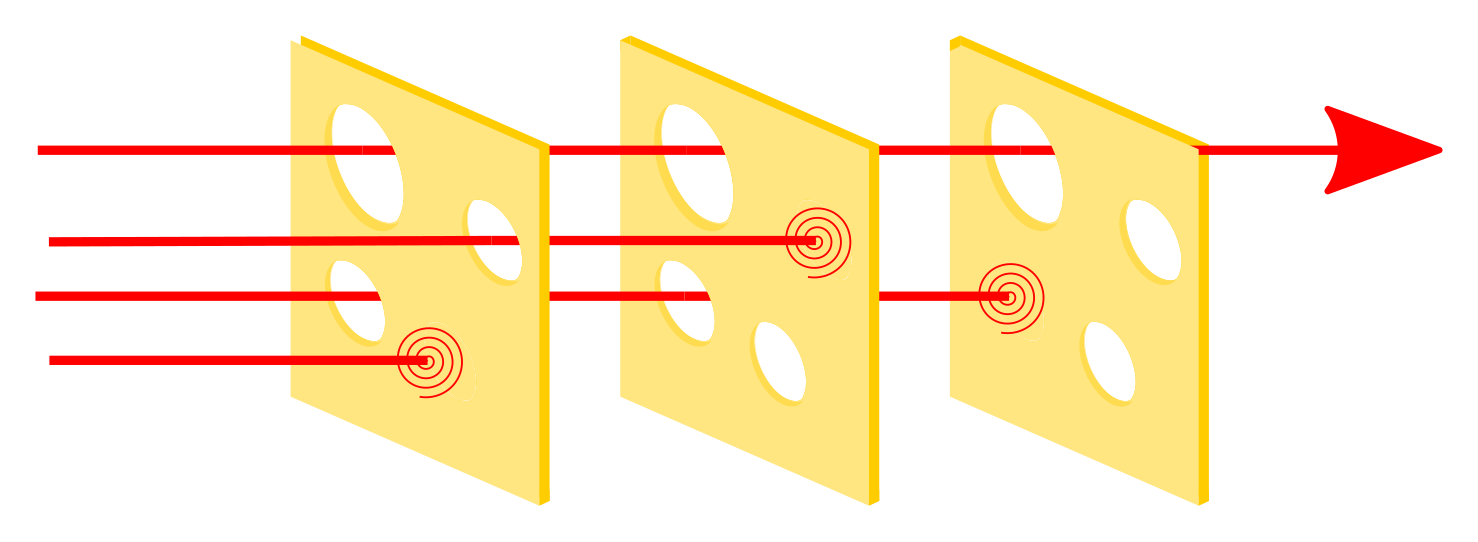

The Swiss Cheese model shows how flaws in each layer of protection can align to allow issues to slip through. We typically apply this model to software security, correctness, and other aspects of the software. However, we can also apply it to ourselves by adopting habits designed to detect issues that automation missed.

In this case, we can think of our reliability tools and our daily practices as a set of Swiss Cheese layers. We have protections in the application and infrastructure layers. We also have observability to detect if those protections are failing. Both the protections and the observability are layers of Swiss Cheese. So, according to the model, we should assume things will slip through each of those layers. The routine assumes issues will slip through; thus, it adds an additional layer of protection in the form of daily, weekly, and bi-weekly habits.

The Routine

So, you now see why we need a routine to supplement automated alerts. Let’s jump into the routine. It consists of tasks that happen at three cadences: a daily glance, a weekly report, and a bi-weekly deep dive.

Daily Glance

The routine starts with a simple daily practice: look at your dashboards. It’s that simple. Just look at them.

I recommend limiting this step to five minutes. You may even want to set a timer to ensure you don’t accidentally spend an hour staring at your dashboards — it’s all too easy to get sucked in.

During this step, you’re looking for anomalies or issues that were not detected by your automated alerts. Remember, our underlying assumption is that our alerts will not detect every issue worth detecting. Issues will slip through the cracks. So, your dashboard scan may look for unexpected changes such as latency or errors that were not detected by alerts.

Weekly Report

The next part of our routine is an automated weekly report of key indicators.

This may simply be a snapshot of a subset of your existing dashboards. The key is to ensure the report is simple enough to scan. So, it should only include your most important metrics.

This weekly report should help you identify trends that are difficult to see at a daily granularity. This might be slowly increasing p99 latency or gradually decreasing request rates.

Bi-Weekly Deep Dive

The third and final part of this routine involves a bi-weekly deep dive where you carefully review any issues encountered.

I recommend dedicating thirty minutes to an hour for this part of the routine. The results will be well worth the time investment. You should also ensure all relevant members of the team are present: engineers, engineering manager, and perhaps even your product manager. The reason for all these people? Awareness. Each engineer gains an understanding of the specific issues and how they were resolved. The managers gain an understanding of the types and severity of issues, enabling them to better prioritize against them.

During this deep dive, the group should review each issue and anomaly that occurred during the shift. You should determine if it was resolved properly or if further work is needed. This is also a good opportunity to check if any monitors or alerts need to be created or adjusted. Your goal is to ensure there is not a repeat of the same issue.

Actions

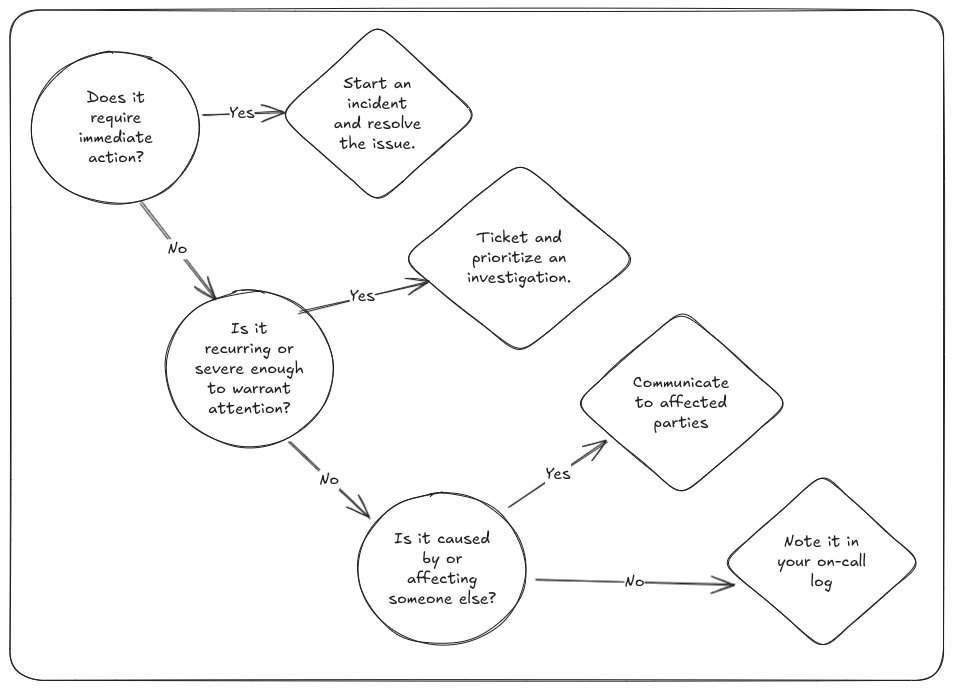

If this routine does its job, you will discover issues. Having a response plan will help you quickly and effectively respond to any issues you encounter.

Ultimately, how you respond will vary greatly depending on the norms within your organization. However, as long as they are acceptable and make sense within your context, I recommend four escalating responses: log, communicate, investigate, and declare incident.

Log

Hopefully, most of the anomalies you notice will not be severe. For these cases, you should still note them in your on-call log. This will provide a valuable history that you can use during your bi-weekly deep dive. In that meeting, you’ll review each of the incidents and decide as a team how to best resolve them long-term.

Communicate

Whenever the issue is caused by or affecting another party, you should proactively communicate the issue to them. This step will vary depending on your organization. But, for example, at The Times, we typically communicate these issues by posting in the relevant Slack channel.

There are two goals of communicating these issues. First, to raise awareness of any issues occurring. Raised awareness often (but not always) leads to raised priority in fixing issues. Second, to ensure the team that caused the issue knows about it, knows it is affecting someone else, and prioritizes a fix.

Investigate

This routine is supposed to be lightweight and quick. So, it does not include time for investigating and fixing issues. Instead, when you find an issue that warrants extended attention, you should record it in your ticketing system (JIRA, Trello, GitHub Projects, etc.) and work with your team to prioritize the investigation and fix.

Since you have already been logging and communicating issues, it should be easier to prioritize the investigation appropriately, since the team and stakeholders will have an awareness of the issue and its severity.

Incident

Occasionally, the routine may uncover severe incidents. In these cases, you should follow your incident management procedure. That may be an official act like declaring a P1 and involving your incident management team or it may be as simple as dropping everything to work on a fix. This greatly depends on your organization’s structure and practices.

Long-Term Goals

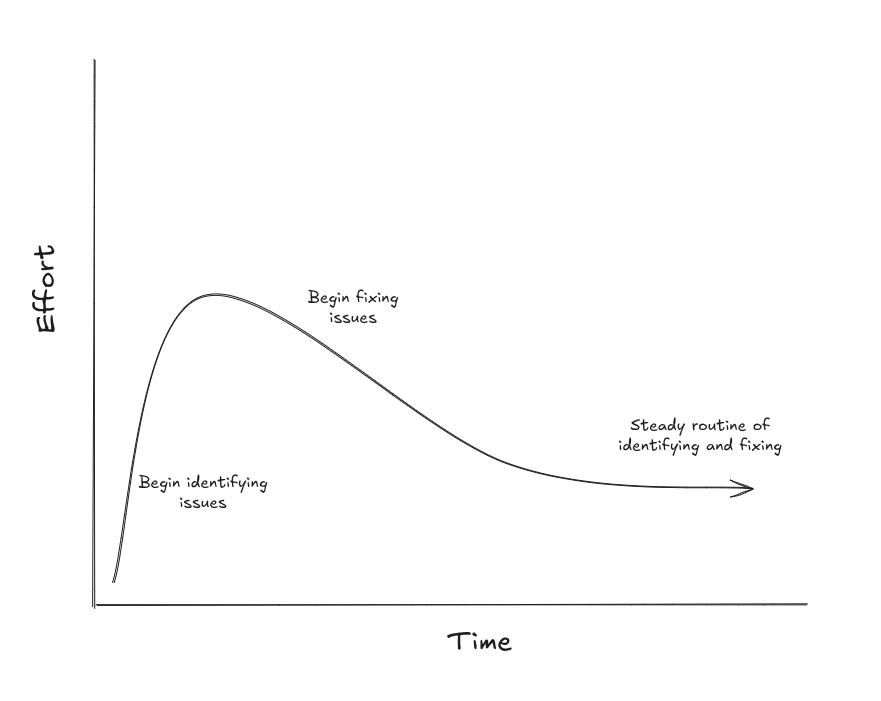

While the routine is permanent, the long-term goal is to reduce the time it requires. The initial rush of issues may overwhelm you. But, over time, you can slowly work down to a steady routine of proactive identification, fixes, and preventions.

This steady investment can help you achieve your long-term goals: no surprises, no repeats, and minimal time investment.

No Surprises

When you look at your dashboards there should be no surprises. Why? Because every issue and anomaly is covered by an alert. By the time you do your daily glance, you are already aware of any issues that occurred. The issues are already logged in your on-call log. Your daily glance should be uneventful and quick.

No Repeats

Whenever an issue does occur it is logged in your on-call log, an investigation is ticketed, a long-term fix is put into place, and alerts are created to automatically fire if it does happen again. If you were to spend this routine repeatedly logging and investigating the same issue, it would be pointless. So, your goal is to use the knowledge of issues in your system to fix them and prevent them from happening again. All issues identified in the future should be novel issues requiring unique fixes.

Any practical engineer should question this policy. “There’s no way all these fixes will be prioritized,” they might say. This is why raising awareness is essential. Since your team is aware of the issues, they may be more likely to prioritize their fixes. When managers are unaware of issues (how often they happen, how severe they are), they are less likely to understand and therefore less likely to be willing to prioritize their fixes.

Minimal Time Investment

Due to the above policy of no surprises and no repeats, the time investment should continually decrease. There will, of course, be an initial surge as you identify issues. However, over time, the investment should continually decrease. Occasionally there may be a new surge in issues but the routine will help you proactively identify and resolve them.

Caveats

There are, of course, many caveats to the above suggestions.

First, I want to be clear that manual checks are a supplement to and not a replacement of automated alerts. Automated alerts are the bedrock of any decent resiliency strategy. Remember, we are only using this routine to catch the cases where issues slip through the cracks of existing monitoring.

Second, it should be understood that simply slapping an alert on everything you identify may lead to a Slack channel or PagerDuty full of flaky alerts. This is why I stress that you must both implement fixes or guardrails as well as alerts. Without both, there is nothing preventing the issue from recurring. Your alerts should help you detect when things that shouldn’t be able to happen—happen.

Third, you should carefully limit the time you spend on this exercise. I recommend actually setting a timer for the daily glance. It is very easy to get sucked into dashboards and spend hours looking at them and adjusting them (or is it just me?).

Fourth, if your effort is going up over time instead of down, you should determine if the routine is actually working for you. If you are spending significant time identifying issues but no time fixing them, then this routine may be pointless. There may be underlying issues your team needs to fix before it can proactively invest in resiliency in this way.

Fifth, this routine cannot help you where you do not have observability. Its entire purpose is to manually and deliberately check your observability. So, wherever you are missing observability, this routine cannot help you. Often, it is where we are lacking observability that we are most at risk—not only of degradation but also of not noticing it at all. So, keep that in mind as you use this routine. Are you seeing everything? Are there any unexplained issues, such as spikes in latency, that have no clear observability indicating why?

Finally, you may not need this routine forever. Eventually, you may find that your system is stable enough to no longer warrant such an investment. Perhaps you have some systems that run nicely in the background while others are constantly being updated. So, you should not indiscriminately apply this routine to every service you maintain. Instead, you should consider it an investment in your critical systems, ones that are at risk of degradation.